Part One: The Illustrious History of Madeira Wine

Part Two: How Sweet Is Madeira Wine?

Part Three: What Makes Madeira Wine Special?

Part Three talked about the unique way in which Madeira wine is aged. However, the labels don’t tend to mention these methods of ageing (estufagem and canteiro) … probably because if you’re not Portuguese, you have no idea how the two words should be pronounced!

Instead, you commonly find these terms:

FRASQUEIRA / GARRAFEIRA

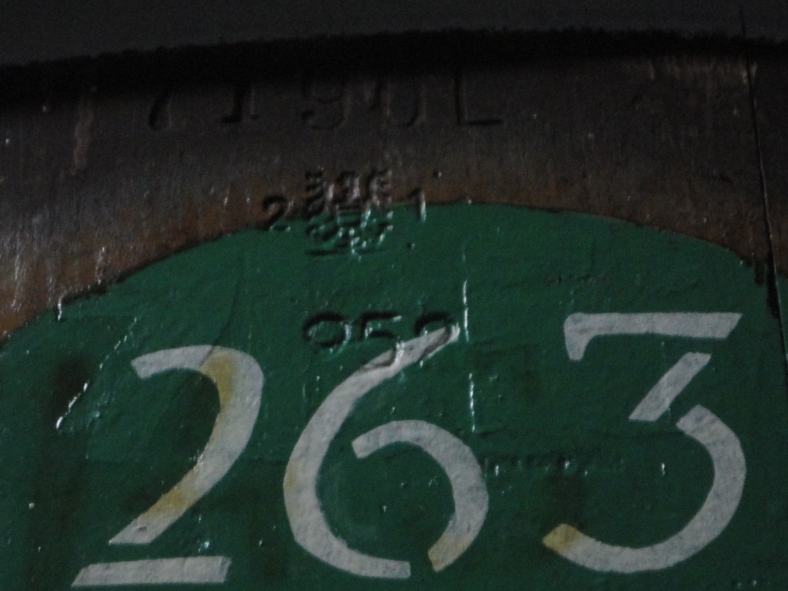

This is the highest quality of Madeira wine. Made from just one grape variety in one particular year, it has been aged for a minimum of 20 years in an oak barrel via the canteiro method. As you can imagine, the production of this kind of wine is extremely limited (normally just 700-800 bottles per producer per year) and therefore most are sold en primeur. It really is something pretty special.

COLHEITA

Also one grape variety and one harvest but a Colheita can be bottled after just 5 years, not 20. Consequently, it is not as rare nor as complex as a Frasqueira but it is fortunately less expensive and still utterly delicious!

Whenever you see a vintage marked on the bottle, this is an indication that it is either a Frasqueira or Colheita.

False!!

BLEND

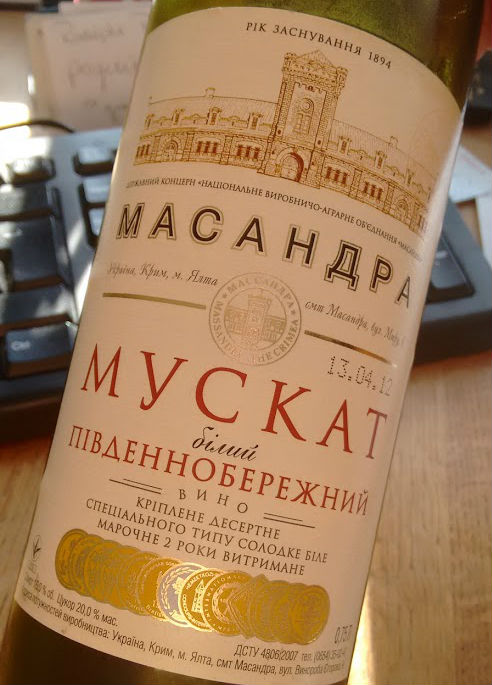

Then there are the blends. These are just blends of different vintages, NOT of grape varieties. (As we said in Part Two, Madeira wines are thankfully single-variety.)

You find the following ages: 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 and now (but only since Jan 2015) 200+ years.

You may have started to nod your head, at this point. However, it’s not that simple. Unlike port, rum or whisky, a 10 year blend of Madeira doesn’t mean that the wine blended in that particular bottle is over ten years old. Nor does it mean that it might be 50% composed of a 8-year-old wine and 50% of a 12-year-old. No, that would be too easy!

Instead, the word “blend” refers to a specific style.

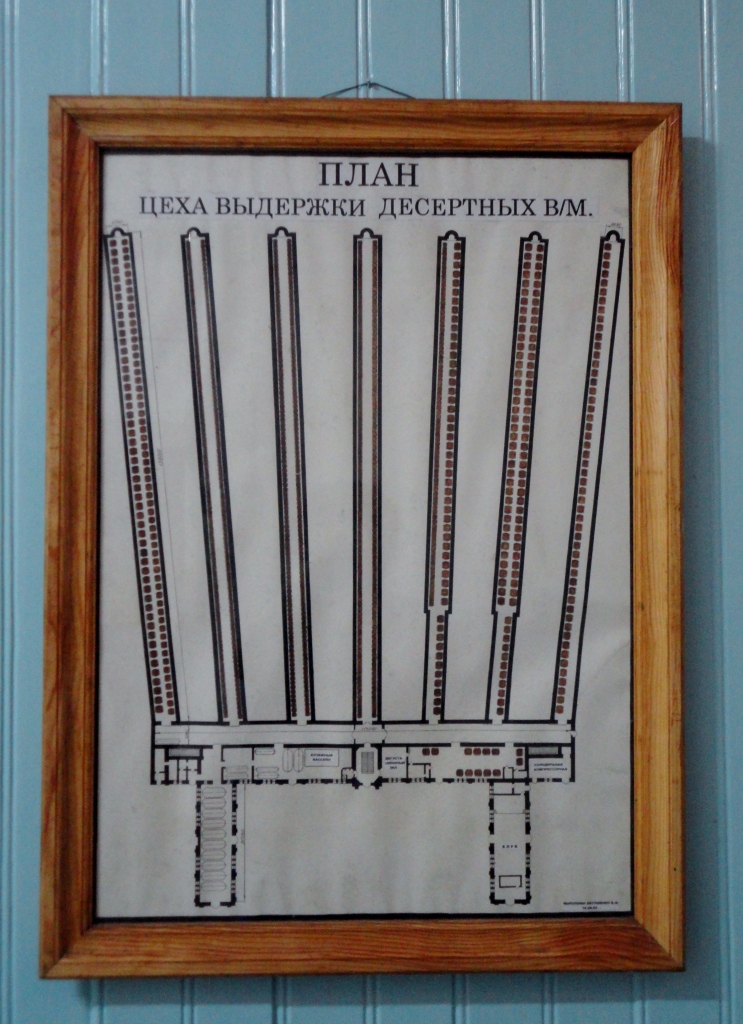

For Madeira wine, there’s a special process. Before bottling, a producer submits a sample of the blend to an independent tasting committee. The committee then asks themselves: “Is this what we expect of a ten year blend?” And this of a 20 year blend?” The answer is a straightforward “yes” or “no“.

“Yes” means the proposed multi-vintage blend can be bottled. “No” means back to the drawing board.

Because this is a little too complicated to explain to the average punter, wineries tend to play up the “aged for five years” card, although this is not strictly correct.

This complicated blending process shows how important it is for each Madeira house to have an excellent master-blender. Not only do the wines have to exhibit a style to please the tasting committee, but they also have to show a distinctive identity for that particular winery.

Think of it how you might analyse developmental characteristics in children… You look for certain traits. How is their hand-eye coordination? Their communication skills? A three year old child behaves differently to a ten year old and very differently from a twenty year old. Now imagine if you have fifty different variables (or in this case, barrels) to pick from in order to compose your style…

Advanced Level Reading

Here are some other terms that you frequently find on Madeira labels, especially in export markets:

Rainwater – a light blended Madeira, made from Tinta Negra, exhibiting a young 3 year old style.

Seleccionado / Selection / Finest – the definition for this is “showing an exceptional quality for its age” … which basically means “marketing blurb.”

Reserve / Reserva – a 5 year old style blend.

Special Reserve / Reserva Especial – a 10 year old style blend, most likely made from one of the more noble grape varieties (i.e. not Tinta Negra) and possibly heated by the canteiro method.

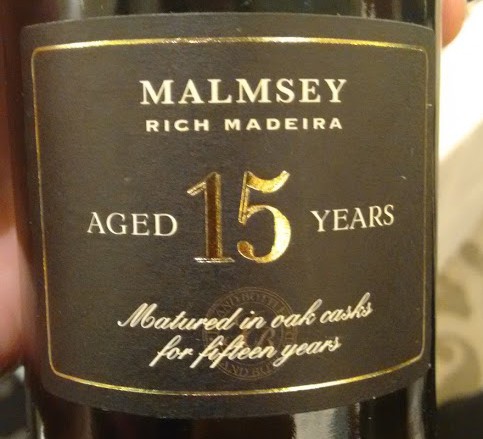

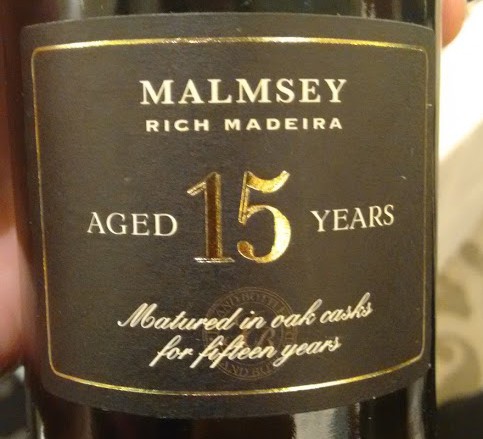

Extra Reserve – a 15 year old style blend, very likely to be a noble grape variety and heated by the canteiro method.

Solera – Before Portugal entered the EU in 1986, it was permitted to produce a Madeira wine with fractional blending (i.e. solera) during the canteiro method. You can still find some old bottles, laid down before the change in legislation took place. Now, although some topping-up is allowed for the Colheita and Frasqueiro, at least 85% has to come from the vintage on the label.

Part Five : coming soon – common mistakes and curious facts about Madeira wine.