Castelcerino is a tiny village situated on the top of the highest point in the Soave hills. It also happens to be where Filippo Filippi lives.

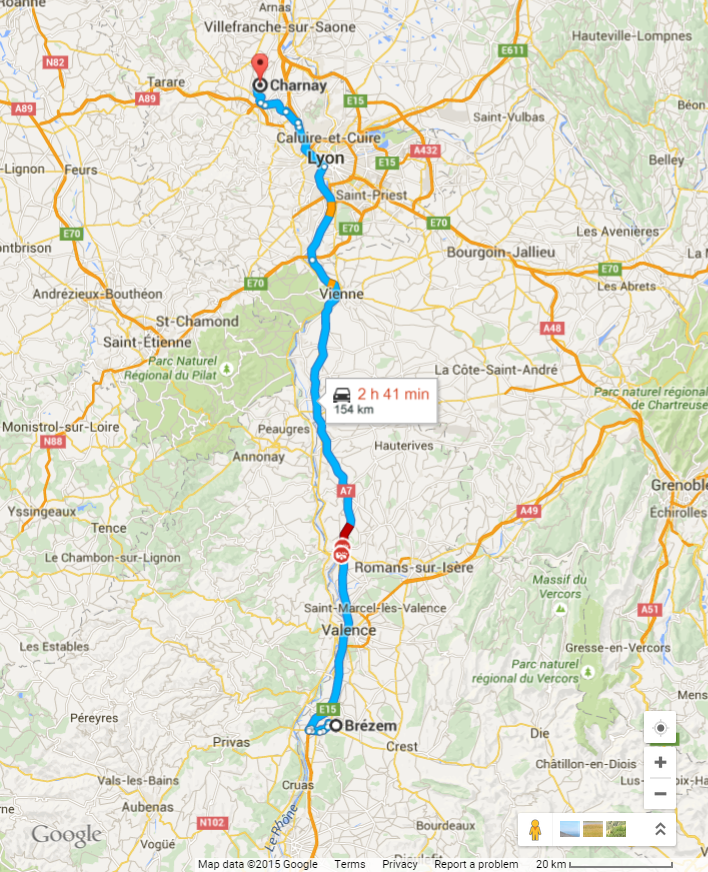

There are two ways to get to Castelcerino. First is to go through the picturesque town of Soave, skirting the mediaeval castle but then tackling a series of perilous hair-pin bends in the climb up to the village. Alternatively, you take the low road a couple of kilometres further through the valley and then turn right, straight up the hill at a gradient which apparently averages +36%!

The first time I came to the Filippi estate was during Vinitaly for a dinner and my GPS took me and my colleague, Marco, up the hair-pin bends. The rental car struggled to get any grit and grind and I’m sure I uttered more than just a few swear words. A couple of months later, I came back with my veteran Renault Clio which subsequently gained the nickname “Super Clio” for its nippy performance up those bends. It was only after a few days that I realised that there was another far less cumbersome route.

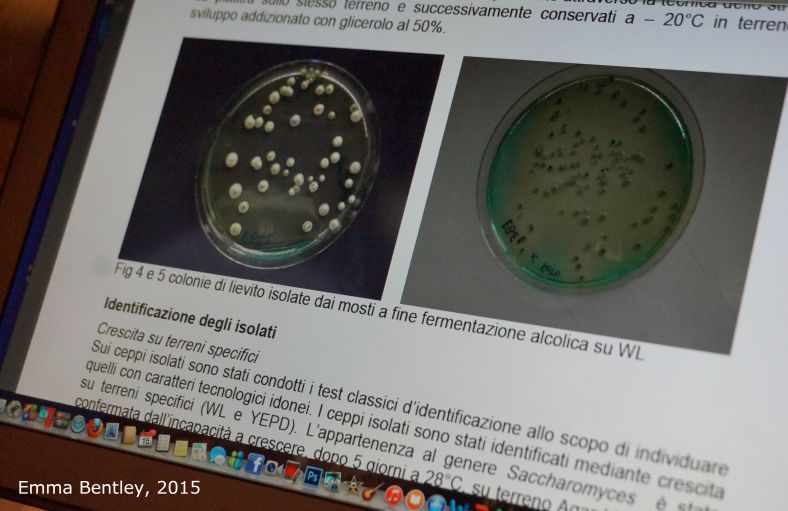

I returned in the middle of September 2015 to get my hands dirty. Harvest started here a couple of weeks ago with the Chardonnay (for Susinaro), the Trebbiano di Soave (for Turbiana) and the Merlot. The Garganega, however, is being particularly problematic. It’s been very, very hot here this year. What rainfall there was, was too little and too late. Subsequently the sugar content is high but the grapes haven’t yet reached full maturity. A hail storm in mid-June didn’t help matters either and some vines are still showing signs of damage.

Healthy but not quite ready… Garganega turns a wonderful salmon pink colour when it is fully ripe.

While we wait for the Garganega, there’s still work to be done in the cellar. There is a rogue steel tank of Trebbiano which needs a remontage morning, noon and night. The Chardonnay is fermenting nicely… but looks like it will get to 13% ABV this year which is higher than normal (but not unusual, given how hot this year has been.)

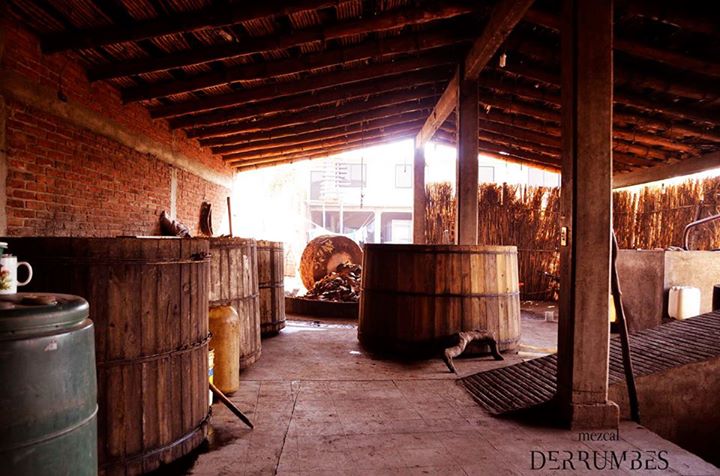

Then there is the Merlot. In previous years, Filippo has made the Merlot into a rosato, under the name Roaron. All change this year as it will become a fully fledged red. It is currently sitting in what can most accurately be described as an over-sized bucket, in which we do a remontage and pigeage (with a large wooden stick) twice a day. “Country style,” Filippo says in English. “Hand-made in Italy,” we joke should be written on the label.

There are just four of us, doing everything from picking to pressing. Even though the Garganega grapes for the dry wines (Castelcerino, Vigne della Bra and Monteseroni) are still not going to be ready for at least another week, there is still harvesting to be done for the Recioto wine.

After each expedition to the vineyards, we stack the boxes in the cellar and leave the grapes to dry out. Meanwhile, we go back to that old routine: pump over the whites, punch down the Merlot, pizza. This was our regime – day in and day out.

You mean you don’t also have a bath tub in your wine cellar….?

On my final morning, I went back to check on the wines. The temperature of the troublesome Trebbiano has fortunately gone down to a more reasonable figure. The Merlot has finished its fermentation and we rack it into a steel tank. It has taken on a beautiful dark garnet colour.

It is so unbelievably peaceful here. As I sit in my make-shift office, with a truly stupdendous view over the adjacent Valipollicella hills and with Verona in the distance, I cast my mind back to the last few days.

It was already pretty clear to me, but I’ve become much more convinced in the benefits of organic agriculture. (I haven’t read or experienced enough to have a completely reasoned opinion of if biodynamics are indeed even better, although I’m inclined to believe that they are.)

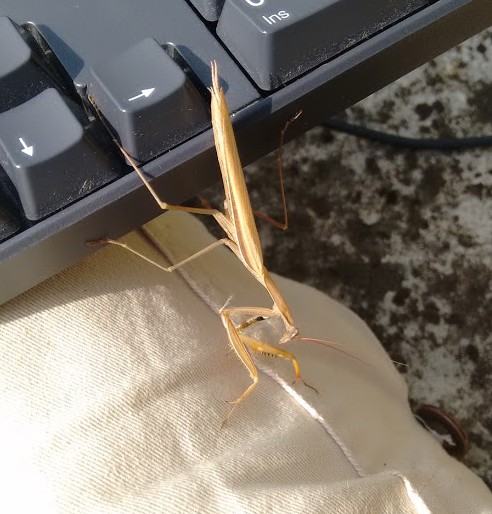

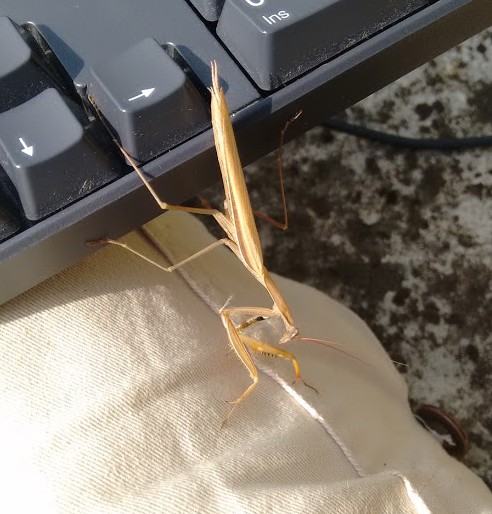

Just while I’ve been writing this post, I’ve spotted six different types of butterfly and had an UFO-insect fly straight into my chest and then spend a couple of moments, sitting on my keyboard, clearly concussed.

Even just a short walk through the vineyards will reveal a mosaic of wildflowers and herbs (especially mint, oregano and rosemary) as well as all the native grasses and even wild hops. I’m also astounded by how much wildlife there is in these woods; I’ve spotted deer, grouse and a snake and seen traces of wild boar. Turns out that wild boar like to munch on any low-hanging grapes… but don’t let the term ‘low-hanging’ fool you. They are easily capable of eating bunches which for me are at waist-height… and I’m five foot nine!

Of all the wineries that I have visited in Italy, the one that sums up true paradise is Tenute Dettori, with its restaurant overlooking the sea. A close second is possibly Andrea Occhipinti’s view over Lake Viterbo in Lazio. (Clearly I have a thing for water!) This, however, is nature.

As I wrote in the first blog post, half of the land here is untouched woodland. Filippo is first and foremost an agrarian and this is very much in evidence. The Turbiana vineyard on the top of the hill, for example, is comprised of two fields, each surrounded by trees and completely isolated. The wind in the trees is echoed by the buzzing of insects in the grass.

The soil is rich too; changing from basalt to clay to seabed within metres. There are grottos with natural spring water. This is the complete anethetis of industrial, modern winemaking and I love it.

As I am packing my bags, I remember a conversation with my colleague Marco in the car on the way up to Filippi the first time. He was explaining to me that Castelcerino was so isolated, perched up there on the hill, that Filippo rarely leaves. Marco’s words resonate with me at that moment. Castelcerino had become my haven too. I don’t want to leave.

Visiting Filippi (May 2015)

Making Recioto di Soave at Filippi (May 2016)

Filippi on Facebook